Education

Education in the largest sense is any act or experience that has a formative effect on the mind, character or physical ability of an individual. In its technical sense, education is the process by which society deliberately transmits its accumulated knowledge, skills and values from one generation to another.

Etymologically, the word education is derived from educare (Latin) "bring up", which is related to educere "bring out", "bring forth what is within", "bring out potential" and ducere, "to lead".[1]

Teachers in educational institutions direct the education of students and might draw on many subjects, including reading, writing, mathematics, science and history. This process is sometimes called schooling when referring to the education of teaching only a certain subject, usually as professors at institutions of higher learning. There is also education in fields for those who want specific vocational skills, such as those required to be a pilot. In addition there is an array of education possible at the informal level, such as in museums and libraries, with the Internet and in life experience. Many non-traditional education options are now available and continue to evolve.

A right to education has been created and recognized by some jurisdictions: since 1952, Article 2 of the first Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights obliges all signatory parties to guarantee the right to education. At world level, the United Nations' International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 guarantees this right under its Article 13.

Contents |

Systems of formal education

Education is a concept, referring to the process in which students can learn something:

- Instruction refers to the facilitating of learning toward identified objectives, delivered either by an instructor or other forms.

- Teaching refers to the actions of a real live instructor designed to impart learning to the student.

- Learning refers to learning with a view toward preparing learners with specific knowledge, skills, or abilities that can be applied immediately upon completion.

Preschool Education

Primary Education

Primary (or elementary) education consists of the first 5–7 years of formal, structured education. In general, main education consists of six or eight years of schooling starting at the age of five or six, although this varies between, and sometimes within, countries. Globally, around 70% of primary-age children are enrolled in primary education, and this proportion is rising.[2] Under the Education for All programs driven by UNESCO, most countries have committed to achieving universal enrollment in primary education by 2015, and in many countries, it is compulsory for children to receive primary education. The division between primary and secondary education is somewhat arbitrary, but it generally occurs at about eleven or twelve years of age. Some education systems have separate middle schools, with the transition to the final stage of secondary education taking place at around the age of fourteen. Schools that provide primary education, are mostly referred to as primary schools. Primary schools in these countries are often subdivided into infant schools and junior school.

Secondary education

In most contemporary educational systems of the world, secondary education comprises the formal education that occurs during adolescence. It is characterized by transition from the typically compulsory, comprehensive primary education for minors, to the optional, selective tertiary, "post-secondary", or "higher" education (e.g., university, vocational school for adults. Depending on the system, schools for this period, or a part of it, may be called secondary or high schools, gymnasiums, lyceums, middle schools, colleges, or vocational schools. The exact meaning of any of these terms varies from one system to another. The exact boundary between primary and secondary education also varies from country to country and even within them, but is generally around the seventh to the tenth year of schooling. Secondary education occurs mainly during the teenage years. In the United States and Canada primary and secondary education together are sometimes referred to as K-12 education, and in New Zealand Year 1-13 is used. The purpose of secondary education can be to give common knowledge, to prepare for higher education or to train directly in a profession.

The emergence of secondary education in the United States did not happen until 1910, caused by the rise in big businesses and technological advances in factories (for instance, the emergence of electrification), that required skilled workers. In order to meet this new job demand, high schools were created and the curriculum focused on practical job skills that would better prepare students for white collar or skilled blue collar work. This proved to be beneficial for both the employer and the employee, because this improvement in human capital caused employees to become more efficient, which lowered costs for the employer, and skilled employees received a higher wage than employees with just primary educational attainment.

In Europe, the grammar school or academy existed from as early as the 16th century; public schools or fee paying schools, or charitable educational foundations have an even longer history.

Higher education

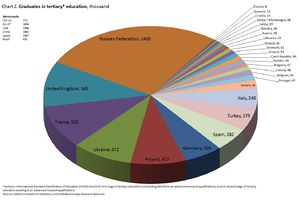

Higher education, also called tertiary, third stage, or post secondary education, is the non-compulsory educational level that follows the completion of a school providing a secondary education, such as a high school, secondary school. Tertiary education is normally taken to include undergraduate and postgraduate education, as well as vocational education and training. Colleges and universities are the main institutions that provide tertiary education. Collectively, these are sometimes known as tertiary institutions. Tertiary education generally results in the receipt of certificates, diplomas, or academic degrees.

Higher education includes teaching, research and social services activities of universities, and within the realm of teaching, it includes both the undergraduate level (sometimes referred to as tertiary education) and the graduate (or postgraduate) level (sometimes referred to as graduate school). Higher education generally involves work towards a degree-level or foundation degree qualification. In most developed countries a high proportion of the population (up to 50%) now enter higher education at some time in their lives. Higher education is therefore very important to national economies, both as a significant industry in its own right, and as a source of trained and educated personnel for the rest of the economy.

Adult education

Adult education has become common in many countries. It takes on many forms, ranging from formal class-based learning to self-directed learning and e-learning. A number of career specific courses such as veterinary assisting, medical billing and coding, real estate license, bookkeeping and many more are now available to students through the Internet.

Alternative education

Alternative education, also known as non-traditional education or educational alternative, is a broad term that may be used to refer to all forms of education outside of traditional education (for all age groups and levels of education). This may include not only forms of education designed for students with special needs (ranging from teenage pregnancy to intellectual disability), but also forms of education designed for a general audience and employing alternative educational philosophies and methods.

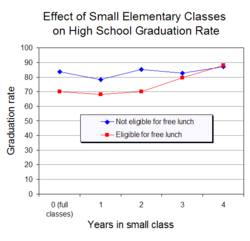

Alternatives of the latter type are often the result of education reform and are rooted in various philosophies that are commonly fundamentally different from those of traditional compulsory education. While some have strong political, scholarly, or philosophical orientations, others are more informal associations of teachers and students dissatisfied with certain aspects of traditional education. These alternatives, which include charter schools, alternative schools, independent schools, and home-based learning vary widely, but often emphasize the value of small class size, close relationships between students and teachers, and a sense of community.

Indigenous education

Increasingly, the inclusion of indigenous models of education (methods and content) as an alternative within the scope of formal and non-formal education systems, has come to represent a significant factor contributing to the success of those members of indigenous communities who choose to access these systems, both as students/learners and as teachers/instructors.

As an educational method, the inclusion of indigenous ways of knowing, learning, instructing, teaching and training, has been viewed by many critical and postmodern scholars as important for ensuring that students/learners and teachers/instructors (whether indigenous or non-indigenous) are able to benefit from education in a culturally sensitive manner that draws upon, utilizes, promotes and enhances awareness of indigenous traditions.[3]

For indigenous students or learners, and teachers or instructors, the inclusion of these methods often enhances educational effectiveness, success and learning outcomes by providing education that adheres to their own inherent perspectives, experiences and worldview. For non-indigenous students and teachers, education using such methods often has the effect of raising awareness of the individual traditions and collective experience of surrounding indigenous communities and peoples, thereby promoting greater respect for and appreciation of the cultural realities of these communities and peoples.

In terms of educational content, the inclusion of indigenous knowledge, traditions, perspectives, worldviews and conceptions within curricula, instructional materials, textbooks and coursebooks have largely the same effects as the inclusion of indigenous methods in education. Indigenous students and teachers benefit from enhanced academic effectiveness, success and learning outcomes, while non-indigenous students/learners and teachers often have greater awareness, respect, and appreciation for indigenous communities and peoples in consequence of the content that is shared during the course of educational pursuits.[4]

The subjects of indigenous cultures, outdoor education and environmental awareness are exceptionally pertinent now that we are in this sixth global species extinction (the Holocene extinction). The term indigenous refers to those cultures who exist and grow naturally in a particular region or country; often called natives. Indigenous cultures usually live in a particular bioregion for many generations and have learned how to live there sustainably. This quality often puts truly indigenous cultures in a unique position in modern times to be aware of and knowledgeable about the interrelationships, needs, benefits and dangers of their bioregion. This is not true of natives whose cultures have been eroded or whom have been displaced. See also Traditional knowledge.

A prime example of how indigenous methods and content can be used to promote the above outcomes is demonstrated within higher education in Canada. Due to certain jurisdictions' focus on enhancing academic success for Aboriginal learners and promoting the values of multiculturalism in society, the inclusion of indigenous methods and content in education is often seen as an important obligation and duty of both governmental and educational authorities.[5]

Process

Curriculum

An academic discipline is a branch of knowledge which is formally taught, either at the university, or via some other such method. Each discipline usually has several sub-disciplines or branches, and distinguishing lines are often both arbitrary and ambiguous. Examples of broad areas of academic disciplines include the natural sciences, mathematics, computer science, social sciences, humanities and applied sciences.[6]

Learning modalities

There has been work on learning styles over the last two decades. Dunn and Dunn[7] focused on identifying relevant stimuli that may influence learning and manipulating the school environment, at about the same time as Joseph Renzulli[8] recommended varying teaching strategies. Howard Gardner[9] identified individual talents or aptitudes in his Multiple Intelligences theories. Based on the works of Jung, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Keirsey Temperament Sorter[10] focused on understanding how people's personality affects the way they interact personally, and how this affects the way individuals respond to each other within the learning environment. The work of David Kolb and Anthony Gregorc's Type Delineator[11] follows a similar but more simplified approach.

It is currently fashionable to divide education into different learning "modes". The learning modalities[12] are probably the most common:[13]

- Visual: learning based on observation and seeing what is being learned.

- Auditory: learning based on listening to instructions/information.

- Kinesthetic: learning based on hands-on work and engaging in activities.

Although it is claimed that, depending on their preferred learning modality, different teaching techniques have different levels of effectiveness,[14] recent research has argued "there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice."[15]

A consequence of this theory is that effective teaching should present a variety of teaching methods which cover all three learning modalities so that different students have equal opportunities to learn in a way that is effective for them.[16] Guy Claxton has questioned the extent that learning styles such as VAK are helpful, particularly as they can have a tendency to label children and therefore restrict learning.[17]

Teaching

Teachers need to understand a subject enough to convey its essence to students. While traditionally this has involved lecturing on the part of the teacher, new instructional strategies such as team-based learning put the teacher more into the role of course designer, discussion facilitator, and coach and the student more into the role of active learner, discovering the subject of the course. In any case, the goal is to establish a sound knowledge base and skill set on which students will be able to build as they are exposed to different life experiences. Good teachers can translate information, good judgment, experience and wisdom into relevant knowledge that a student can understand, retain and pass to others. Studies from the US suggest that the quality of teachers is the single most important factor affecting student performance, and that countries which score highly on international tests have multiple policies in place to ensure that the teachers they employ are as effective as possible.[18] With the passing of NCLB in the United States (No Child Left Behind), teachers must be highly qualified.

Technology

Technology is an increasingly influential factor in education. Computers and mobile phones are used in developed countries both to complement established education practices and develop new ways of learning such as online education (a type of distance education). This gives students the opportunity to choose what they are interested in learning. The proliferation of computers also means the increase of programming and blogging. Technology offers powerful learning tools that demand new skills and understandings of students, including Multimedia, and provides new ways to engage students, such as Virtual learning environments. Technology is being used more not only in administrative duties in education but also in the instruction of students. The use of technologies such as PowerPoint and interactive whiteboard is capturing the attention of students in the classroom. Technology is also being used in the assessment of students. One example is the Audience Response System (ARS), which allows immediate feedback tests and classroom discussions.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) are a “diverse set of tools and resources used to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information.”[19] These technologies include computers, the Internet, broadcasting technologies (radio and television), and telephony. There is increasing interest in how computers and the Internet can improve education at all levels, in both formal and non-formal settings.[20] Older ICT technologies, such as radio and television, have for over forty years been used for open and distance learning, although print remains the cheapest, most accessible and therefore most dominant delivery mechanism in both developed and developing countries.[21]

The use of computers and the Internet is in its infancy in developing countries, if these are used at all, due to limited infrastructure and the attendant high costs of access. Usually, various technologies are used in combination rather than as the sole delivery mechanism. For example, the Kothmale Community Radio Internet uses both radio broadcasts and computer and Internet technologies to facilitate the sharing of information and provide educational opportunities in a rural community in Sri Lanka.[22] The Open University of the United Kingdom (UKOU), established in 1969 as the first educational institution in the world wholly dedicated to open and distance learning, still relies heavily on print-based materials supplemented by radio, television and, in recent years, online programming.[23] Similarly, the Indira Gandhi National Open University in India combines the use of print, recorded audio and video, broadcast radio and television, and audio conferencing technologies.[24]

The term "computer-assisted learning" (CAL) has been increasingly used to describe the use of technology in teaching.

Educational theory

Education theory is the theory of the purpose, application and interpretation of education and learning. Its history begins with classical Greek educationalists and sophists and includes, since the 18th century, pedagogy and andragogy. In the 20th century, "theory" has become an umbrella term for a variety of scholarly approaches to teaching, assessment and education law, most of which are informed by various academic fields, which can be seen in the below sections.

Economics

It has been argued that high rates of education are essential for countries to be able to achieve high levels of economic growth.[25] Empirical analyses tend to support the theoretical prediction that poor countries should grow faster than rich countries because they can adopt cutting edge technologies already tried and tested by rich countries. However, technology transfer requires knowledgeable managers and engineers who are able to operate new machines or production practices borrowed from the leader in order to close the gap through imitation. Therefore, a country's ability to learn from the leader is a function of its stock of "human capital".[26] Recent study of the determinants of aggregate economic growth have stressed the importance of fundamental economic institutions[27] and the role of cognitive skills.[28]

At the individual level, there is a large literature, generally related back to the work of Jacob Mincer,[29] on how earnings are related to the schooling and other human capital of the individual. This work has motivated a large number of studies, but is also controversial. The chief controversies revolve around how to interpret the impact of schooling.[30]

Economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis famously argued in 1976 that there was a fundamental conflict in American schooling between the egalitarian goal of democratic participation and the inequalities implied by the continued profitability of capitalist production on the other.[31]

History

The history of education according to Dieter Lenzen, president of the Freie Universität Berlin 1994, "began either millions of years ago or at the end of 1770". Education as a science cannot be separated from the educational traditions that existed before. Adults trained the young of their society in the knowledge and skills they would need to master and eventually pass on. The evolution of culture, and human beings as a species depended on this practice of transmitting knowledge. In pre-literate societies this was achieved orally and through imitation. Story-telling continued from one generation to the next. Oral language developed into written symbols and letters. The depth and breadth of knowledge that could be preserved and passed soon increased exponentially. When cultures began to extend their knowledge beyond the basic skills of communicating, trading, gathering food, religious practices, etc., formal education, and schooling, eventually followed. Schooling in this sense was already in place in Egypt between 3000 and 500BC.

Nowadays some kind of education is compulsory to all people in most countries. Due to population growth and the proliferation of compulsory education, UNESCO has calculated that in the next 30 years more people will receive formal education than in all of human history thus far.[32]

Philosophy

Philosophy of education is the philosophical study of the purpose, process, nature and ideals of education. Philosophy of education can naturally be considered a branch of both philosophy and education. Philosophy of education is commonly housed in colleges and departments of education, yet it is applied philosophy, drawing from the traditional fields of philosophy (ontology, ethics, epistemology, etc.) and approaches (speculative, prescriptive, and/or analytic) to address questions regarding education policy, human development, education research methodology, and curriculum theory, to name a few.

Psychology

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. Although the terms "educational psychology" and "school psychology" are often used interchangeably, researchers and theorists are likely to be identified as educational psychologists, whereas practitioners in schools or school-related settings are identified as school psychologists. Educational psychology is concerned with the processes of educational attainment in the general population and in sub-populations such as gifted children and those with specific disabilities.

Educational psychology can in part be understood through its relationship with other disciplines. It is informed primarily by psychology, bearing a relationship to that discipline analogous to the relationship between medicine and biology. Educational psychology in turn informs a wide range of specialities within educational studies, including instructional design, educational technology, curriculum development, organizational learning, special education and classroom management. Educational psychology both draws from and contributes to cognitive science and the learning sciences. In universities, departments of educational psychology are usually housed within faculties of education, possibly accounting for the lack of representation of educational psychology content in introductory psychology textbooks (Lucas, Blazek, & Raley, 2006).

Sociology

The sociology of education is the study of how social institutions and forces affect educational processes and outcomes, and vice versa. By many, education is understood to be a means of overcoming handicaps, achieving greater equality and acquiring wealth and status for all (Sargent 1994). Learners may be motivated by aspirations for progress and betterment. Education is perceived as a place where children can develop according to their unique needs and potentialities.[34] The purpose of education can be to develop every individual to their full potential. The understanding of the goals and means of educational socialization processes differs according to the sociological paradigm used.

Education in the Developing World

In developing countries, the number and seriousness of the problems faced are naturally greater. People in more remote or agrarian areas are sometimes unaware of the importance of education. However, many countries have an active Ministry of Education, and in many subjects, such as foreign language learning, the degree of education is actually much higher than in industrialized countries; for example, it is not at all uncommon for students in many developing countries to be reasonably fluent in multiple foreign languages, whereas this is much more of a rarity in the supposedly "more educated" countries where much of the population is in fact monolingual.

Universal primary education is one of the eight Millennium Development Goals and great improvements have been achieved in the past decade, yet a great deal remains to be done.[35] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute indicate the main obstacles to greater funding from donors include: donor priorities, aid architecture, and the lack of evidence and advocacy.[35] Additionally, Transparency International has identified corruption in the education sector as a major stumbling block to achieving Universal primary education in Africa.[36] Furthermore, demand in the developing world for improved educational access is not as high as one would expect as governments avoid the recurrent costs involved and there is economic pressure on those parents who prefer their children making money in the short term over any long-term benefits of education. Recent studies on child labor and poverty have suggested that when poor families reach a certain economic threshold where families are able to provide for their basic needs, parents return their children to school. This has been found to be true, once the threshold has been breached, even if the potential economic value of the children's work has increased since their return to school.

A lack of good universities, and a low acceptance rate for good universities, is evident in countries with a high population density. In some countries, there are uniform, over structured, inflexible centralized programs from a central agency that regulates all aspects of education.

- Due to globalization, increased pressure on students in curricular activities

- Removal of a certain percentage of students for improvisation of academics (usually practised in schools, after 10th grade)

India is now developing technologies that will skip land based phone and internet lines. Instead, India launched EDUSAT, an education satellite that can reach more of the country at a greatly reduced cost. There is also an initiative started by the OLPC foundation, a group out of MIT Media Lab and supported by several major corporations to develop a $100 laptop to deliver educational software. The laptops are widely available as of 2008. The laptops are sold at cost or given away based on donations. These will enable developing countries to give their children a digital education, and help close the digital divide across the world.

In Africa, NEPAD has launched an "e-school programme" to provide all 600,000 primary and high schools with computer equipment, learning materials and internet access within 10 years. Private groups, like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, are working to give more individuals opportunities to receive education in developing countries through such programs as the Perpetual Education Fund. An International Development Agency project called nabuur.com, started with the support of former American President Bill Clinton, uses the Internet to allow co-operation by individuals on issues of social development.

Internationalization

Education is becoming increasingly international. Not only are the materials becoming more influenced by the rich international environment, but exchanges among students at all levels are also playing an increasingly important role. In Europe, for example, the Socrates-Erasmus Programme[37] stimulates exchanges across European universities. Also, the Soros Foundation [38] provides many opportunities for students from central Asia and eastern Europe. Programmes such as the International Baccalaureate have contributed to the internationalisation of education. Some scholars argue that, regardless of whether one system is considered better or worse than another, experiencing a different way of education can often be considered to be the most important, enriching element of an international learning experience.[39]

See also

- For a topical guide to this subject, see Outline of Education.

- Academic dishonesty

- Adult education

- Alternative education

- Autodidacticism

- Behavior modification

- Classical education

- Classroom of the future

- Collaborative learning

- Comparative education

- Curriculum

- Curriculum studies

- Developmental Education

- Distance education

- e-learning

- Education Day

- Education Index

- Education reform

- Educational animation

- Educational psychology

- Educational research

- Educational technology

- Entrepreneurship education

- Experiential education

- Gifted education

- Glossary of education-related terms

- Graduate education

- History of education

- Home schooling

- Indoctrination

- Instructional technology

- Language education

- Learning

- Learning 2.0

- Learning by teaching (LdL)

- Learning community

- Learning sciences

- Legal education

- Life skills

- Lifelong education

- Medical education

- MyEdu

- Online learning community

- Over-education

- Peace education

- Pedagogy

- Philosophy of education

- Public education

- Religious education

- Remedial education

- Residential education

- School

- School of the Future

- Single-sex education

- Socialization

- Sociology of education

- Special education

- Synchronous learning

- Taxonomy of Educational Objectives

- Teacher

- Tertiary education

- Traditional knowledge

- Tutoring

- University

- Virtual education

- Vocational education

References

- ↑ Etymonline.com

- ↑ UNESCO, Education For All Monitoring Report 2008, Net Enrollment Rate in primary education

- ↑ See Merriam et al. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007). Sharan Merriam, Rosemary Caffarella and Lisa Baumgartner write that “we need only look more closely inside our own borders, to Native Americans, for example… to find major systems of thought and beliefs embedded in entirely different cultural values and epistemological systems that can be drawn upon to enlarge our understanding of adult learning” (p. 218). Merriam et al. then go on to explain that another purpose in becoming familiar with other knowledge systems is the benefit this knowledge will have in affecting our practice with learners having other than Western worldviews. Antone and Gamlin (2004) for example, argue that to be effective, literacy programs with Aboriginal people (a term they use to refer to First Nations, Inuit, and Metis persons and collectivities) must be more than ‘reading, numeracy and writing which is typically geared towards gaining access to mainstream employment’ (p. 26). Rather Aboriginal literacy is about sustaining a particular worldview and about the survival of a distinct and vital culture. Being literate is about resymbolizing and reinterpreting past experience, while at the same time honoring traditional values. Being literate is about "living" these values in contemporary times. Being literate is about "visioning" a future in which an Aboriginal "way of being" will continue to thrive. Meaningful Aboriginal literacy will develop and find expression in everything that is done. Consequently, Aboriginal literacy programs must reflect a broad approach that recognizes the unique ways that Aboriginal people represent their experience and knowledge. [p. 26; italics in original] Frequently, Merriam et al. also return to this need “to enlarge our understanding of adult learning” through the lens of cultural sensitivity by focusing on theories related to the intimate connection between learning and social context– often framed in terms of inclusiveness and respect for differing values, beliefs, experiences, perspectives and environments as strongly correlated with the traditional ways and methods inherent in both individual and collective notions of culture. For instance, in their discussion of experiential learning, the authors comment that “in acknowledging cognition and learning from experience as a cultural phenomenon, the perspectives of critical… and postmodern thinkers become crucial. Among the major results of thinking about cognition from a cultural frame are the critiques that have been fostered about traditional educational theory and practice… Foremost among these critiques is a challenge to the fundamental notion that learning is something that occurs within the individual. Rather, learning encompasses the interaction of learners and the social environments in which they function” (p. 180).

- ↑ See generally R. A. Malatest et al. Best Practices in Increasing Aboriginal Post-secondary Enrollment Rates (Canada: Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, 2002) CMEC.ca and Dr. Pamela Toulouse, Supporting Aboriginal Student Success: Self-Esteem and Identity, A Living Teachings Approach (Presentation delivered at the 2007 Ontario Education Research Symposium), EDU.gov.on.ca

- ↑ In the Canadian province of Manitoba for instance, collaborative efforts between the government and post-secondary institutions (both universities and colleges) has resulted in the implementation of 13 Access Programs (spanning several disciplines and program focus areas). These Access programs often place emphasis on indigenous methods and content in the delivery of post-secondary education and training, while also providing students with a variety of other culturally sensitive supports (such as elders and mentors) in order to enhance their success in higher education. Advocates of such programs will often highlight the fact that, between 2001/02 and 2005/06 (most recent available data) a total of 800 students successfully graduated from these programs with post-secondary credentials, while an average of 70.8 per cent of all students enrolled during these same years were Aboriginal. Statistics cited according to pp. 141–143 of the Manitoba Council on Post-Secondary Education Statistical Compendium For the Academic Years Ending in 2006[1] According to these advocates, the inclusion of indigenous models of education in those Access Programs that are intended for Aboriginal learners, is an important factor contributing to the completion of post-secondary education for the estimated 566 Aboriginal students who would not otherwise have been likely to achieve this same level of success.

- ↑ "Examples of subjects". Curriculumonline.gov.uk. http://www.curriculumonline.gov.uk/Default.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ "Dunn and Dunn". Learningstyles.net. http://www.learningstyles.net/. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ "Biographer of Renzulli". Indiana.edu. http://www.indiana.edu/~intell/renzulli.shtml. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Thomas Armstrong's website detailing Multiple Intelligences

- ↑ "Keirsey web-site". Keirsey.com. http://www.keirsey.com/. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ "Type Delineator description". Algonquincollege.com. http://www.algonquincollege.com/edtech/gened/styles.html. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Swassing, R. H., Barbe, W. B., & Milone, M. N. (1979). The Swassing-Barbe Modality Index: Zaner-Bloser Modality Kit. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser.

- ↑ Priscilla Theroux (2004-04-26). "Varied Learning Modes". Members.shaw.ca. http://members.shaw.ca/priscillatheroux/styles.html. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Barbe, W. B., & Swassing, R. H., with M. N. Milone. (1979). Teaching through modality strengths: Concepts and practices. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser,

- ↑ Pashler, Harold; McDonald, Mark; Rohrer, Doug; Bjork, Robert (2009), "Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence", Psychological Science in the Public Interest 9 (3): 105-119

- ↑ "Learning modality description from the Learning Curve website". Library.thinkquest.org. http://library.thinkquest.org/C005704/content_hwl_learningmodalities.php3. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ "Guy Claxton speaking on What's The Point of School?". dystalk.com. http://www.dystalk.com/talks/49-whats-the-point-of-school. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ↑ How the world's best school systems come out top

- ↑ Blurton, Craig. "New Directions of ICT-Use in Education" (PDF). http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/lwf/dl/edict.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ↑ ICT in Education

- ↑ Potashnik, M. and Capper, J.. "Distance Education:Growth and Diversity" (PDF). http://www.worldbank.org/fandd/english/pdfs/0398/0110398.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ↑ Taghioff, Daniel. "Seeds of Consensus—The Potential Role for Information and Communication Technologies in Development.". Archived from the original on 2003-10-12. http://web.archive.org/web/20031012140402/http://www.btinternet.com/~daniel.taghioff/index.html. Retrieved 2003-10-12.

- ↑ Open University of the United Kingdom Official website

- ↑ Indira Gandhi National Open University Official website

- ↑ Hanushek, Economic Outcomes and School Quality

- ↑ UCLA Economics 183 Lecture from Professor Boustan

- ↑ Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation." American Economic Review 91,no.5 (December 2001):1369–1401.

- ↑ Eric A. Hanushek, and Ludger Woessmann, "The role of cognitive skills in economic development." Journal of Economic Literature 46,no.3 (September 2008):607–608.

- ↑ Jacob Mincer, "The distribution of labor incomes: a survey with special reference to the human capital approach." Journal of Economic Literature 8,no.1 (March 1970):1–26.

- ↑ See, for example, David Card, "Causal effect of education on earnings," in Handbook of labor economics, edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David Card. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1999:1801–1863; James J. Heckman, Lance J. Lochner, and Petra E. Todd., "Earnings functions, rates of return and treatment effects: The Mincer equation and beyond," in Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by Eric A. Hanushek and Finis Welch. Amsterdam: North Holland, 2006:307–458.

- ↑ Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life (Basic Books, 1976)

- ↑ Robinson, K.: Schools Kill Creativity. TED Talks, 2006, Monterrey, CA, USA.

- ↑ Finn, J. D., Gerber, S. B., Boyd-Zaharias, J. (2005). Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 214–233.

- ↑ Schofield, K. (1999). "The Purposes of Education", Queensland State Education: 2010, [Online] URL: www.aspa.asn.au/Papers/eqfinalc.PDF [Accessed 2002, Oct 28]

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Liesbet Steer and Geraldine Baudienville 2010. What drives donor financing of basic education? London: Overseas Development Institute.

- ↑ http://www.transparency.org/news_room/latest_news/press_releases/2010/2010_02_23_aew_launch_en

- ↑ "Socrates-Erasmus Programme". Erasmus.ac.uk. http://www.erasmus.ac.uk. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ "Soros Foundation". Soros.org. http://www.soros.org/. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ Dubois, H. F. W., Padovano, G., & Stew, G. (2006) Improving international nurse training: an American–Italian case study. International Nursing Review, 53(2): 110–116.

External links

- Education at the Open Directory Project

- Educational Resources from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics: International comparable statistics on education systems

- OECD education statistics

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||